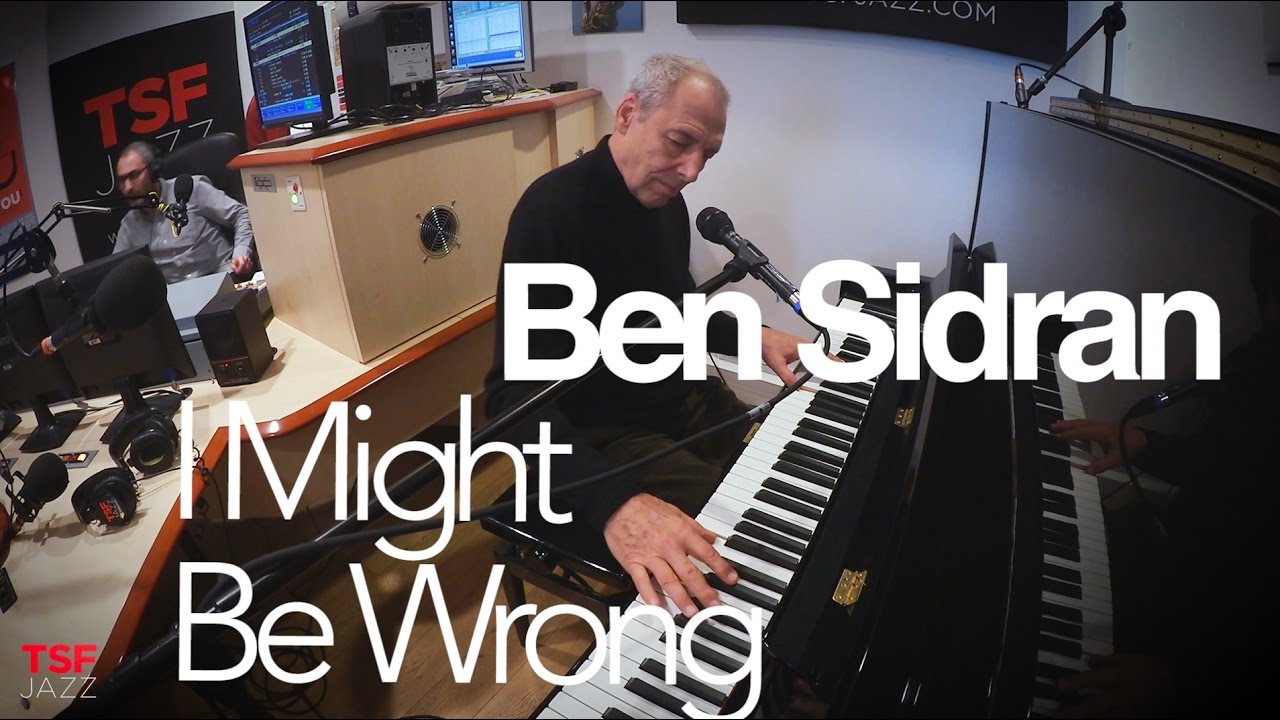

Photo via All About Jazz – allaboutjazz.com

They sang out, in voices of many echoes—airy, haunting, jaunty, imploring, wistful, lonely, spiraling, seductive and in harmonies as plummy as they were piquant.

Yes, jazz musicians in 2025 often chose to top off their ensembles with singers, sometimes the leader themselves, a bandmember or special guest. I heard it so increasingly in the last few years that it seems more than a trend, perhaps a collective cultural movement, to persuade a distracted public that this “intellectual” American sonic art form can be as human as any.

And as democratic as any. These underlying qualities persist in jazz even within another emerging trend, ensembles larger to orchestral. But these add up to another essay topic, at least.

Among the best albums I heard that carried the v for voice was a British one, Every Journey, by the 11-member Ensemble C, as transporting an album as I heard in 2025. This one, like some others, had a vocalist, sometimes wordless, as part of every tune, floating or soaring over or through the instruments. Here, Brigitte Beraha sang tales from bandleader-composer Claire Cope’s investigation of women pioneers, both in death-defying adventures and historic breakthroughs, going back several centuries.

Potently, Poignantly

Others, like my best-album list topper, This Rock We’re On: Imaginary Letters by Mike Holober & The Gotham Jazz Orchestra, uses Jamile Staevie Ayres’s voice selectively, but potently, poignantly. Here the ensemble is also the voice as are instrumental soloists. This two-CD work, lyrical and craggy, is inspired by great environmentalists (Rachel Carson, Ansel Adams, Sigurd Olson, Wendell Berry), with music and lyrics (mostly) by Holober, a previous Grammy Award nominee.

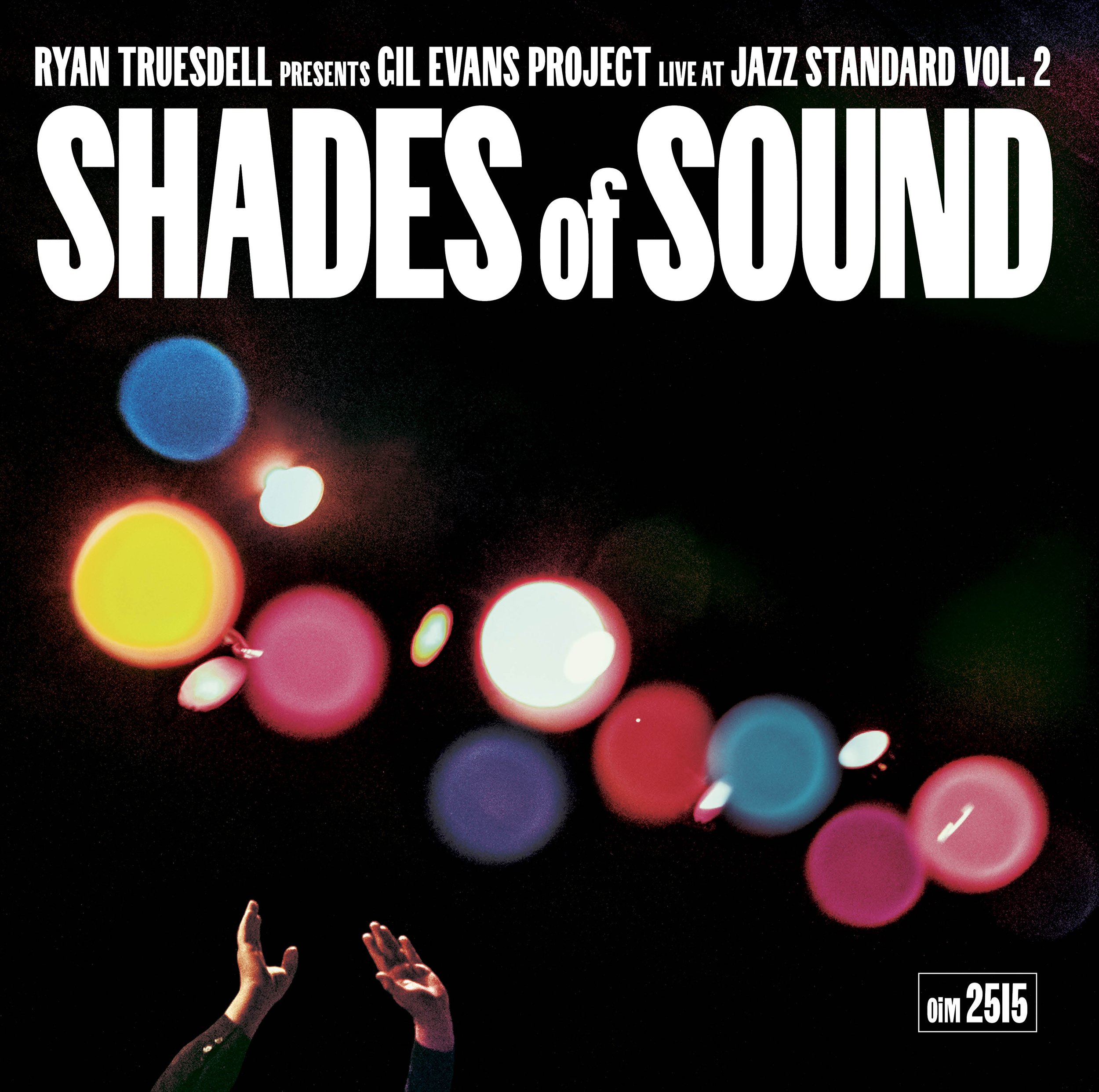

Shades of Sound by the ever-sumptuous Gil Evans Project (led by Verona WI native Ryan Truesdell), had a guest singer, Wendy Giles, on several orchestrated songs, especially on “Laughing at Life,” a fresh-breath salve for these troubled times.

Cover: allaboutjazz.com.

Another, Suspended in Time, a song cycle by Rondi Charleston and pianist Fred Hersch, was born of a therapy journal she began in the time-freezing pandemic, but which gradually acquired life and breadth of its own, with vocals by Kate McGarry and Gabrielle Stravelli. Another emotionally-loaded album was Breathe: Music for Large Ensembles by Peter Lenz, reflecting his ongoing struggle with lung cancer, and, yes, with a vocalist, Efrat Elony.

Another woman who, like Cope and Charleston, conceived an ambitious album is singer-songwriter Lorraine Feather on The Green World. Like Holober, she explores our environmental marvels and mysteries but also plays on contemporary social dynamics between the sexes, with a wit surfacing like sly weeds here and there.

Lorraine Feather. Courtesy https://alchetron.com/Lorraine-Feather

Time will tell, but a mature art form like jazz frankly needed a fresh gambit at least to rekindle general interest as competition for pervasive entertainment, much less political or cultural enlightenment, intensified in the Internet age.

Wisconsin Jazz

As a postscript of honorable mentions, I celebrate the work of Wisconsin jazz artists, a still under-appreciated species. The big name, two-time Grammy Award-winning trumpeter Brian Lynch (no relation to this writer), continued his authoritative brio on 7x7x7.

Soft Rock by Madison bassist-composer John Christensen proves jazz fusion still plays a distinctively electrified role in the jazz soundscape.

Pianist-composer Tim Whalen’s Trio Vol. 1, with Christensen and increasingly first-call drummer Hannah Johnson, proved as impressive a Wisconsin jazz piano trio album as I can recall in some years.

The irrepressibly swinging Johnson also drove percussion for the quartet Heirloom, on their debut album, cannily titled Familiar Beginnings, but as sparkling and satisfying as a vintage Milwaukee lager.

_____________________